As many a former smoker will probably attest, quitting cigarettes ranks high in the hard-to-kick category. I made several unsuccessful attempts before finally kicking the habit after a 10 year pack-a-day run. Ultimately what worked for me was to go cold turkey, but there were perhaps other alternatives which I might have tried. In a paper from Nature Neuroscience, researchers from University of Michigan provided participants with interventions involving individually tailored messages* designed to encourage quitting and found that participants’ brain activity while listening to the messages predicted how likely they would be to successfully quit smoking.

*Tailored messages are statements about an individuals’ issues and thoughts about quitting smoking, derived from pre-screen interviews with them. e.g., “You are worried that when angry or frustrated, you may light up”.

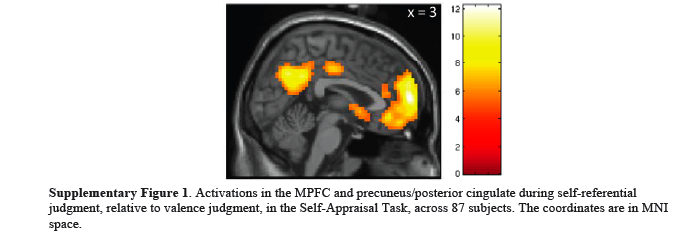

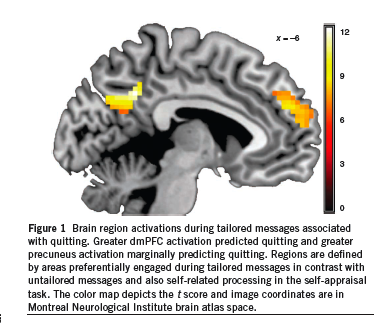

Here’s the premise: Anti-smoking messages custom made for an individual can be more effective than generic ones, but only if said individual processes those messages in a self directed manner. Past research has shown a specific set of neural regions – primarily the mPFC and precuneus/posterior cingulate – to be associated with self referential thinking. Therefore, researchers hypothesized, activity in these brain regions while processing tailored anti-smoking messages might predict the likelihood of quitting.

The Study

The experiment was carried out over three days with a follow-up visit four months later.

Day 1: 91 participants completed a health assessment, demographic questionnaire and a psychosocial characteristics scale related to quitting smoking. Responses were then used to create smoking cessation messages tailored to each individual.

Day 2: Participants went into scanner and performed 2 fMRI tasks: The first task had participants listen to anti-smoking messages of three different types: personally tailored anti-smoking, non-tailored anti-smoking and neutral.

Here are some examples of what they heard:

Tailored messages

A concern you have is being tempted to smoke when around other smokers.

Something else that you feel will tempt you after you quit is because of a craving.

You are worried that when angry or frustrated, you may light up.

Untailored messages

Some people are tempted to smoke to control their weight or hunger.

Smokers also light up when they need to concentrate.

Certain moods or feelings, places, and things you do can make you want to smoke.

Neutral messages

Oil was formed from the remains of animals and plants that lived millions of years ago.

Sighted in the Pacific Ocean, the world’s tallest sea wave was 112 feet.

Wind is simple air in motion. It is caused by the uneven heating of the earth’s surface by the sun.

Then, participants completed a self appraisal task to identify brain regions active during self relevant thought processes. In this task, participants saw adjectives appear on the screen and had to either rate how much the adjective described them or whether the adjective was positive or negative.

Day 3: Participants completed a web-based smoking cessation program and were instructed to quit smoking. (They were given a supply of nicotine patches to get themselves started)

Results

Behavioral

Experimenters checked in with subjects four months later to see if they were abstaining from smoking. Out of 87 who participated in the smoking cessation program, 45 were not smoking, while 42 were still (or had quit briefly and restarted) smoking.

Subjects were given a surprise memory test for the anti-smoking messages they’d received four months prior and remembered self relevant, tailored messages most well. However, their memory performance was not related to whether they successfully quit smoking.

fMRI

As for the fMRI data, experimenters used a mask of tailored vs. untailored message conditions AND self-appraisal to identify the region common to both processes. This seems like a mild case of double dipping, no? That is, finding a brain region that responds to the condition of interest (in this case, voxels more active in tailored vs. untailored conditions) and then using the same data to test the hypothesis. Ideally, the ROI would be obtained independently of the main task.

A blow by blow on the different contrasts of interest:

1. Researchers looked at brain regions more active during tailored vs. untailored messages and found differential activation in the regions below.

There are, I think, some problems here; mainly, that the task differences for processing tailored vs non-tailored statements may extend beyond self relevant thinking to (1) memory processes employed in processing either category of stimuli; that is, episodic (tailored) vs. semantic (non-tailored), (2) cognitive effort, (3) elicitation of visual vs. non-visual memory, (4) processing fluency and (5) affect or reward responses. Thus, the difference in brain activation found in this task might reflect something other than just self referential processing.

2. The localizer task (used to isolate neural areas involved in self appraisal) had participants process adjectives either by relating them to self or by judging their affective value. This suggests an alternative explanation for the categorical contrast in that it isn’t specific to self per se, but really more specific to people vs. non-people. A more widely used version of this task has participants process adjectives with regards to self or an other. As a further control, a third condition is often included in which participants identify whether words are in upper case or lower case. The contrast applied is (self – control) – (other – control). It’s not clear why the researchers chose the task they did, which seems significantly noisier.

Here’s the contrast from the present study:

And here’s a contrast from another study (Jenkins 2010) that looked at three different types of self-referential processing.

Although roughly similar, the current study shows cortical midline activation seems to be much more dorsal than that found in Jenkins (2010). Using an ROI derived from this localizer task to correlate neural activity in tailored vs. untailored statements with quitting led to a non-significant result (from supplementary materials). This could explain why the researchers used the composite mask to define the ROI.

3. Again, the primary ROI was defined as a composite of overlapping regions between the self reference task AND the tailored vs. untailored statements task, which was used to compare neural activity with quitting behavior. They found that activity in these regions – which included dmPFC, precuneus and angular gyrus – during tailored smoking cessation messages predicted the likelihood of successfully abstaining from smoking. dmPFC and precuneus activation also individually predicted smoking cessation success, although angular gyrus did not.

This study provides clear evidence that participants processed tailored vs. non-tailored messages about smoking differently, and that this difference corresponded to their ability to stop smoking. However,

(1) neither task effectively isolates self referential processing,

(2) the region of activation was much more dorsal than that usually found in this literature (Northoff & Bermpohl, 2004; Schneider et al.,2008; Uddin, Iacoboni, Lange, & Keenan, 2007; Gillihan & Farah, 2005),

(3) an independently obtained ROI yielded insignificant results and

(4) mPFC and precuneus subserve an untold number of cognitive processes beyond self reflection.

Therefore, it seems a bit of a stretch to claim the neural activation found in this study is indicative of self referential processing.

References

Chua HF, Ho SS, Jasinska AJ, Polk TA, Welsh RC, Liberzon I, & Strecher VJ (2011). Self-related neural response to tailored smoking-cessation messages predicts quitting. Nature neuroscience, 14 (4), 426-7 PMID: 21358641

Jenkins AC, & Mitchell JP (2010). Medial prefrontal cortex subserves diverse forms of self-reflection. Social neuroscience, 1-8 PMID: 20711940

Northoff, G. (2005). Emotional-cognitive integration, the self, and cortical midline structures Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28 (02) DOI: 10.1017/S0140525X05400047

Gillihan, S., & Farah, M. (2005). Is Self Special? A Critical Review of Evidence From Experimental Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience. Psychological Bulletin, 131 (1), 76-97 DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.1.76

SCHNEIDER, F., BERMPOHL, F., HEINZEL, A., ROTTE, M., WALTER, M., TEMPELMANN, C., WIEBKING, C., DOBROWOLNY, H., HEINZE, H., & NORTHOFF, G. (2008). The resting brain and our self: Self-relatedness modulates resting state neural activity in cortical midline structures Neuroscience, 157 (1), 120-131 DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.014

UDDIN, L., IACOBONI, M., LANGE, C., & KEENAN, J. (2007). The self and social cognition: the role of cortical midline structures and mirror neurons Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11 (4), 153-157 DOI: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.01.001